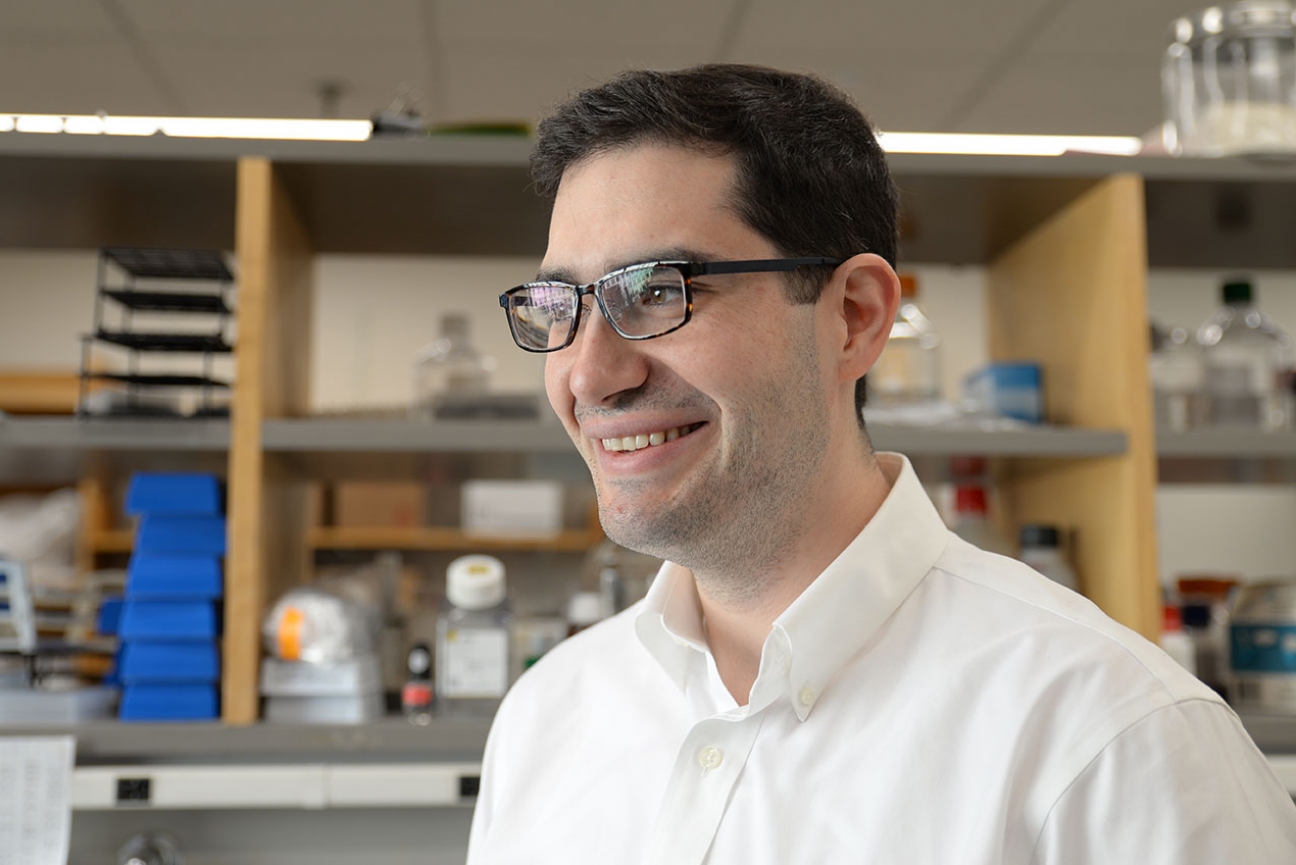

Whitehead Institute postdoctoral researcher Isaac Klein

Conor Gearin/Whitehead Institute

Meet a Whitehead Postdoc: Isaac Klein

Isaac Klein is a postdoc in Whitehead Institute Member Richard Young’s lab who is investigating mechanisms of gene transcription. He is also a medical oncology clinical fellow at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute. We sat down with Klein to learn more about him and his experiences in and out of the lab.

What do you investigate?

Rick’s lab studies transcription and how gene expression is controlled. About two years ago, the lab started studying something called phase separation in this context. Phase separation is the process by which proteins and other molecules form liquid droplets, which we think of as membraneless organelles, inside cells. Cells use these droplets to concentrate proteins and other molecules without actually enclosing them inside a membrane. We have been investigating the role that phase separation plays in concentrating proteins involved in transcription of the genome, and also how the droplets, which we call condensates, help those proteins regulate gene expression. My focus is cancer, so I am now studying how this process is altered in malignancy. I’m trying to find out if there’s any way to perturb phase separated droplets to disrupt cancer cell growth and survival.

What would you like people outside of your field to know about phase separation?

The field of phase separation has really revolutionized the way we look at how a cell is organized and structured. In high school we learned about the organelles within the cell: the nucleus, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum. Now we’re finding that there are probably hundreds of other little structures inside the cell that aren't as simple or well-defined as the classic organelles, but are no less important and serve many of the same functions of compartmentalization and localization.

When you were a kid, what did you want to be when you grew up?

I was a very tall kid. On the first day of kindergarten, the teacher pulled my mom aside and said, “He's too big for kindergarten. He should go to first grade.” I guess back then that was acceptable. So my mom pulled me aside and said, “Isaac, the teacher said that you're so big you should go to first grade. Is that OK with you?” And I don’t remember this, but apparently, I told my mom, "Yeah, it's OK; that means I'll start medical school a year earlier."

What led you to become both a practicing physician and a basic researcher?

In college I ran away from the premed crowd. I’m driven by curiosity and the process of asking questions, and I felt that the premed culture was not focused on curiosity so much as it was on achievement. Instead, I majored in biological and environmental engineering. When I finished college I took a job in a laboratory as a technician, and I just happened to work with an MD-PhD. At that time, I still hadn't decided exactly what I wanted to do, go to medical school or get a PhD, and just working in a lab with someone who did both showed me that was an option. So I ended up getting an MD-PhD.

What is your experience of balancing clinical work and research?

I see patients half a day a week at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute, the rest of the time I’m here doing science. It can be difficult to juggle, but I work with a truly remarkable team here at Whitehead Institute, and our cooperation makes everything possible. I try to keep my clinical practice and expertise very focused; I only see patients with breast cancer. This allows me to compartmentalize my clinical work a little bit so that I have the bandwidth and energy to spend most of my time in lab asking basic science questions. Whitehead Institute is a basic science institution, that's part of its character. I came here because I wanted to work where there aren't a lot of physicians bringing a clinical perspective to the science. I thought I could have more of an impact in that kind of environment. Basic science is the driver of so much of what we know in medicine, so to be here working on basic questions, thinking about how we can impact patients five, ten, or twenty years from now is an exciting and privileged position.

How do you handle the stress of your job?

My amazing wife, Ellie, is the answer to all questions that involve how I do anything.

What are your hobbies outside of work?

I have two young children, so I don’t have any hobbies. They occupy most of my limited time outside of work. We like to spend time together as a family: movie night, cooking dinner together, when it’s nice outside barbecuing or having a bonfire in the backyard. We also raise chickens in our backyard.

What is it like raising chickens?

This started when I was a first-year oncology fellow. I was spending fourteen hours a day taking care of really sick cancer patients. I felt like I needed some kind of outlet, so I took up carpentry and I built a coop in my backyard. Then we got chickens. They're actually really easy to take care of. All you have to do is keep them fed and watered, and they produce delicious fresh eggs for you. That's it. Once in a while you have to clean out the coop, and you have to make sure things stay nice and secure. It's a passive hobby.

What’s been your biggest disaster in the lab?

Before I had kids, I did have a hobby. I brewed beer. One day in grad school I was home making a batch of beer, and after I bottled it, I came into the lab to split cells. A couple of days pass, and on Monday morning I arrive to find that everyone is freaking out because all the cells are contaminated with brewer's yeast. I must have carried some of the yeast that I used to make the beer on my hands, and it got into the incubator. All of the contaminated tissue culture dishes smelled like bread and beer. People were not happy. Everything went in the trash.

What research questions are you most excited about?

There's a whole world of proteins that we know are important for cancer cells to grow and spread through the body but that have been really difficult to drug. What we're learning in this new field of phase separation, as it relates to transcriptional control, is that many of these proteins form these phase-separated droplets. That knowledge gives us a new avenue by which we can think about perturbing their function and drugging them. The idea that this new understanding, this new model, can give us a lever to pull in targeting those proteins is really exciting, especially for someone who takes care of a lot of patients who need more treatment options.

Where do you see yourself in ten years?

I try not to think about myself in a specific job. The world of science and medicine are so big and move so quickly, how can anyone predict where we will be in ten years? I just hope I’m asking and answering questions that move science forward and advancing our ability to improve patients' lives. Where and how that's done is anybody's guess, but I’m looking forward to finding out!

Topics

Contact

Communications and Public Affairs

Phone: 617-452-4630

Email: newsroom@wi.mit.edu