Researchers Piece Together Cancer Puzzle

Note: This study was retracted at the request of the Authors.

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — About four years ago, a group of researchers at Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research created the first genetically engineered human cancer cells in the lab to study early disease development. They infected normal cells in mice with cancer-causing genes, and waited for tumors to form. Some cells formed large tumors. But others yielded only small, harmless bumps, much to the scientists’ surprise.

What went wrong? they wondered. Or, from the perspective of a group of scientists who’d like to figure out how to keep cancer from spreading, What went right?

“We had these two cell types that for all intents and purposes were the same,” said Randolph Watnick, lead researcher on the project and postdoctoral associate in the lab of Whitehead Member Robert Weinberg. Only one thing set them apart: One had high levels of a mutated protein involved in tumor cell and blood vessel growth, while the other had low levels. Still, Watnick maintained, since most human tumors have low levels of this mutated protein, “they both should have been able to form tumors.”

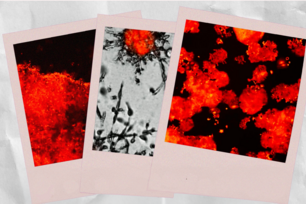

Watnick knew what the end result looked like, but was missing key pieces to the puzzle. He decided to examine the systems involved with blood vessel growth—a process called angiogenesis. In a healthy body, two types of proteins keep this system in balance: Growth factors that turn the process on and anti-angiogenic factors that turn the process off. But in cancer patients, one or both of these switches can malfunction, leading to the uncontrolled growth of blood vessels that not only deliver nutrients crucial for cancer cell growth, but also give the cells a conduit through which they can travel around the body, possibly spreading the disease to vital organs.

Watnick uncovered a previously unknown pathway used by cancer cells to control the system that regulates blood vessel growth and throw it out of balance. The study, published earlier this year in the journal Cancer Cell, identifies a communications channel used to turn off the expression of Tsp-1, a key anti-angiogenic protein. With this protein out of commission, the ingrowth of new blood vessels into the tumor proceeds unchecked, leading to tumor growth. For Watnick, the pieces of the puzzle began to fit together.

“He found that the cells that were unable to form tumors actually send out a rather strong anti-angiogenetic signal that precludes the formation of blood vessels,” explained Weinberg, whose lab studies how cancer develops and spreads.

Now that the pathway has been revealed, researchers want to know more about the signals it carries. In September, Watnick will join Harvard Medical School as an assistant professor in the Surgical Research department. He plans to examine this new pathway further, a project that could lead to a new protein target for drug development.

![]()

Topics

Contact

Communications and Public Affairs

Phone: 617-452-4630

Email: newsroom@wi.mit.edu