Noncoding RNAs alter yeast phenotypes in a site-specific manner

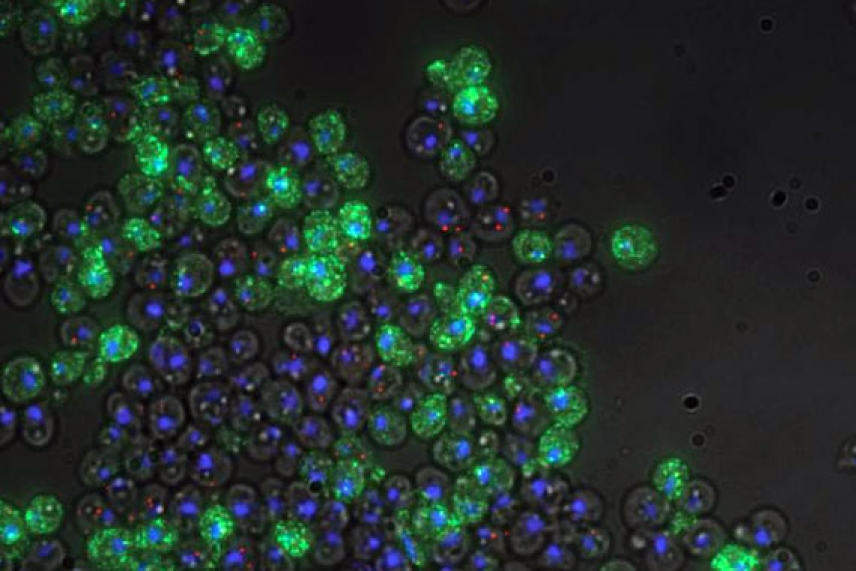

Brewer’s yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) cells expressing the long noncoding RNA ICR1 (red) have the FLO11 gene (green) switched off. Nuclei are stained blue.

Courtesy of Molecular Cell

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. – Personal change can redefine or even save your life—especially if you are one of a hundred yeast cell clones clinging to the skin of a grape that falls from a sun-drenched vine into a stagnant puddle below. By altering which genes are expressed, cells with identical genomes like these yeast clones are able to survive in new environments or even perform different roles within a multicellular organism.

Changes in gene expression can occur in a multitude of ways, but a team of scientists from Whitehead Institute and other institutions has used single-cell imaging and computational approaches, along with more traditional molecular biology techniques, to demonstrate for the first time that brewer's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) cells rely on two competing long intergenic noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) as a location-dependent switch to toggle between a sticky and a non-sticky form.

"This validates the observations from a previous paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) and provides a new way of looking at the process of gene expression," says Whitehead Founding Member Gerald Fink.

The switch turns on and off the FLO11 gene, which determines whether a yeast cell exists in a free-floating form or an alternative form that sticks to other cells and colonizes substrates. In fungal pathogens such as Candida albicans, genes related to FLO11 allow the invaders to form dangerous biofilms that stick to catheters and other medical devices.

This FLO11 switch is composed of two ncRNAs encoded upstream of the FLO11 promoter, a section of DNA that acts as a docking site for transcription factors that increase or repress FLO11's expression. Although noncoding RNAs constitute the vast majority of RNAs, they do not produce proteins but instead play various mechanistic roles, including modifying chromatin, enhancing or repressing transcription, and promoting messenger RNA (mRNA) degradation, to affect a cell's gene expression.

In the earlier PNAS paper, Stacie Bumgarner, then a Fink lab graduate student, implicated two upstream ncRNAs, Interfering Crick RNA (ICR1) and Promoting Watson RNA (PWR1), in FLO11 expression. But the techniques available to her at the time lacked the resolution required to observe these ncRNAs at the level of the single cell. Most traditional molecular biology techniques that assay RNA expression generate data that provides only a glimpse of the average RNA transcript levels across a population of cells. But because populations of yeast contain some cells that are active and others that are inactive for FLO11 transcription at the same time, single-cell resolution was required to probe deeply the role of the ncRNAs ICR1 and PWR1 in regulating FLO11 expression.

In collaboration with scientists at MIT and the Broad Institute, Bumgarner recently analyzed the RNA contents of thousands of individual yeast cells to see how these two ncRNAs affect FLO11 production in each of the cells. Their work is published in the February 24 issue of the journal Molecular Cell.

"In a single cell, one can visualize an individual mRNA molecule and count the total number of each of these non-coding RNA species in every cell in the population," says Gregor Neuert, co-first-author of the Molecular Cell paper and a postdoctoral researcher in the lab of MIT physics professor Alexander van Oudenaarden. "By investigating single-cells, one gains detailed insight into gene regulation which goes beyond the average RNA expression measured on population of cells."

Instead of finding the average number of FLO11, ICR1, and PWR1 mRNAs for the entire population, Bumgarner and Neuert could visualize how much variation occurred between cells, from cells with no copies of a particular RNA to cells with multiple copies of that RNA.

Using this data, Bumgarner and colleagues formulated a model for a location-dependent switch wherein the ncRNAs use their own transcription to turn FLO11 on and off.

"It's not that the ncRNAs, as RNA products themselves, do something—it's the act of transcription in that particular site, so the site matters," says Bumgarner, a co-first-author of the Molecular Cell article. "You can kind of imagine the DNA as a railroad track, and the transcriptional machinery as a train moving down the track. The way we understand it, the train moving down the track is tossing off all of the transcription factors sitting on the DNA."

In Bumgarner's model, when ICR1 is transcribed, its transcription machinery knocks off any transcription factors from the FLO11 promoter, effectively stopping FLO11's transcription and resetting its promoter. To ultimately promote FLO11 transcription, PWR1 runs ICR1's transcription machinery off the DNA, thereby preventing ICR1 from clearing the FLO11 promoter.

"These noncoding RNAs are unusual, because to the best of our knowledge, they act only on the DNA strand that they're from," says Fink. "In many of the other systems that people have identified, the noncoding RNAs seem to act all over the place in the genome."

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the National Science Foundation (NSF), and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG).

* * *

Gerald Fink's primary affiliation is with Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, where his laboratory is located and all his research is conducted. He is also a professor of biology at Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

* * *

Citation:

Bumgarner, S. L., Neuert, G., Voight, B. F., Symbor-Nagrabska, A., Grisafi, P., van Oudenaarden, A., & Fink, G. R. (2012). Single-cell analysis reveals that noncoding RNAs contribute to clonal heterogeneity by modulating transcription factor recruitment. Molecular Cell, 45(4), 470-482.

Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research is a nonprofit, independent research and educational institution. Wholly independent in its governance, finances and research programs, Whitehead shares a close affiliation with Massachusetts Institute of Technology through its faculty, who hold joint MIT appointments.

Topics

Contact

Communications and Public Affairs

Phone: 617-452-4630

Email: newsroom@wi.mit.edu