Getting Distance: Runners at Whitehead

This story is part of our ongoing series, Beyond the Lab Bench. Click here to see all stories in this collection.

The challenges of completing a research project are often compared to a marathon. But it’s not just a metaphor: many biologists are distance runners. Whitehead Institute researchers often look to several miles along the Charles to sort out how to solve a problem—or just to take a break and get out in nature.

“Science is a culture in which you tolerate delayed gratification, and that’s also very true for long-distance running,” says Whitehead Fellow Kristin Knouse, who has been a runner since middle school. “They enrich for the same personality. The person who’s going to go run 20 miles is doing it because after those 20 miles, you feel really good. You’re really in it for that end result. That’s also what draws and keeps us in science.”

Lukas Chmatal, a postdoc in the Page lab and an ultramarathon runner, described the phenomenon in statistical terms. “There’s a significant enrichment of runners among scientists,” he says. “I think that reflects that successful scientists are characterized by endurance and perseverance, which is what running embraces.”

Running has long been a part of the fabric of Whitehead Institute. Paging through back issues of the Whitehead Bulletin newsletter reveals past running teams from the Institute, including a group of 34 runners that placed 4th out of 500 in the 2001 Chase Corporate Challenge, a 3.5 mile race. The team included Whitehead Institute Member David Sabatini and Cafeteria Manager Jim Nally.

Photo credit: Whitehead Bulletin

Chmatal explains that being a runner has many benefits. “It definitely helps to get distance from an issue,” he says. “Sometimes you feel like you are too submerged in your thoughts about an issue, and running can provide that distance for a fresh view. Plus, when you run with someone else, you can get someone else’s perspective.”

Last year, Chmatal ran in the Boston marathon along with his lab mate, graduate student Alexander Godfrey. Chmatal set his personal record for the marathon with a time of 3:01. His other marathon routes had been flatter—Boston is a famously hilly marathon—so he analyzed his training to see what he did differently.

“It was not my heaviest training in terms of the mileage or speed work,” Chmatal says. “I had many other training periods before with higher numbers. But what was standing out from last year’s training was the time I allowed myself to rest and recover after runs.”

Left: Lukas Chmatal finishes the 2019 Boston Marathon holding a Czech flag. Right: Chmatal runs an ultramarathon in the Swiss Alps. Photos: Courtesy of Lukas Chmatal

Whitehead Institute researchers continue to band together to take on ambitious events. One relay race drew together members of several different labs for a 200 mile road race: the 2018 Ragnar Relay in New Hampshire, which begins in the White Mountains and goes all the way to the coast. Whitehead Institute Fellow Kristin Knouse began organizing a 12-person team to compete even before she arrived to begin her fellowship. The team name: Beaver Fever, after the M.I.T. mascot.

“When I was starting at Whitehead, I thought this would be a great way to bring labs together, have people get to know each other, and a great way for me to meet people,” Knouse says.

To make it through the 200 miles, each team member had to run three routes of 3-10 miles. After dropping off a runner for a route, the team van then had to make it to the next drop-off point at the right time.

“You have to be pretty strategic because you drop them off, they start running, and then you need to estimate how long it will take them to run so that you get to the next exchange point before they do,” Knouse says. “There are a lot of unknowns there. The running and driving paths are sometimes very different. They may run faster than you expect, or they might get lost along the way.”

Elena Kingston, a graduate student in the Bartel lab, joined the team. “It was definitely challenging, because you don’t sleep that much,” she says. “You’re trying to perform at your peak without having rested. But it’s a lot of fun hanging out with a bunch of people in a van, alternating running and sleeping.”

“There’s a kind of camaraderie that comes out of that shared challenge,” Knouse says. “It builds a lot of connections. Half the time we were talking about science and experiments, and half the time we were strategizing how to get ahead of the next team—or lamenting how miserable we were at 3 a.m., running in the dark, on no sleep.”

The 2018 Whitehead Institute team at the finish of the Ragnar Relay in New Hampshire. Photo: courtesy of Kristin Knouse.

Opinions varied on whether it was fun to run on nocturnal mountain roads.

“Sebastian [Lourido] had the time of his life running at night,” Knouse says. “But as I was running through several miles of New Hampshire backroads in the dark, the entire time I was thinking this is either going to be the end of me or it’s going to be a really cool experience. Now that I’ve survived, it was a really cool experience.”

The team finished 19th out of 453 teams, completing the 200 miles in 25:43:45.

Of course, most running takes the form of routine runs on local paths. Kingston prefers to run in the morning. “If I don’t run before I come to work, the day can get kind of carried away,” she says. “It puts you in a clear headspace for the day, and then you can focus on your work.”

Cambridge is a nice place to be a runner, Kingston says. “I run along the Charles River,” she says. “What’s nice, especially as a woman runner, is that at most times of day there’s a good number of people there, so you never feel totally alone. That can be kind of challenging during the winter with snow. During some snowstorms I’ve run laps around M.I.T.’s campus, because they’re really good at shoveling the sidewalks.”

The Bartel lab features a number of runners, and they often run together in the Cambridge half marathon and other local road races.

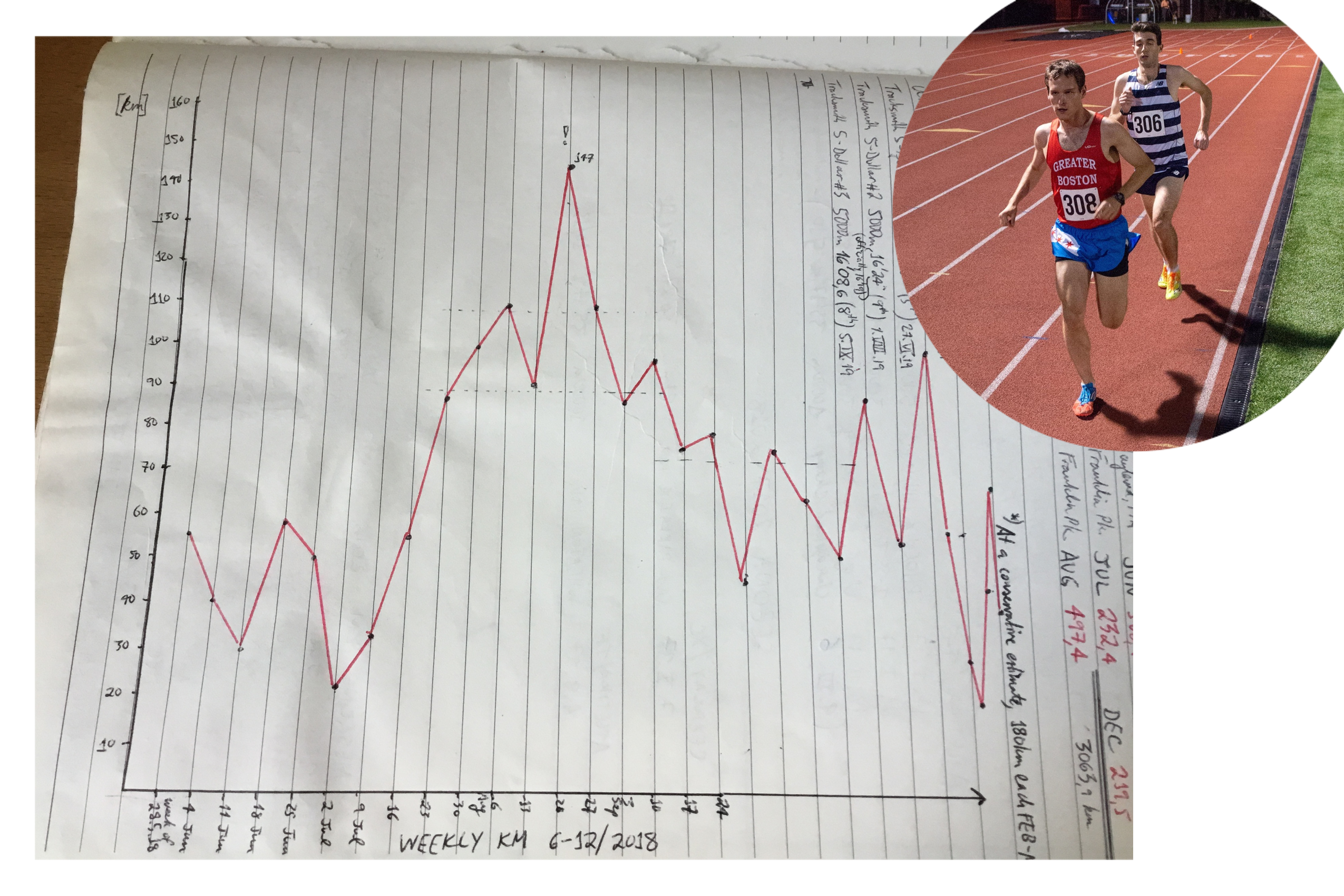

Michael Stubna, a graduate student in the Bartel lab, understands the importance of remaining consistent while training. “Even before I intended to become a scientist, running has been something I’ve quantified,” Stubna says. “I have a number of notebooks that detail every training run I’ve done since December 2009, along with graphs and statistics and whatnot—so it’s something I’ve always treated very seriously.” He has carried on the same format as his father’s running log from the ’70s and ’80s.

A graph of Michael Stubna’s training runs (in km) each week from June to December 2018. Inset: Stubna competes in a 5K race in summer 2019. Photos: courtesy of Michael Stubna

Stubna raced in college track and cross country. He now competes with the Greater Boston Track Club. “Boston has a very mature competitive club running scene,” he says. Stubna’s favorite events are track races of 3K, 5K, and 10K. The focus on track running has given him a precise sense of pace.

“The most important thing I’ve learned to do in competitive running is to judge pace,” he says. “If you told me to go on a track in 70 seconds versus 72 seconds, I could do that. For the longer races, that’s even more important. There’s a very fine line between starting too quickly and too slowly.”

That sense for pace translates well into structuring one’s progress through a research project. “Whether you’re completing a postdoc or a PhD, it’s certainly better to have a marathon mentality and not a sprint mentality,” Stubna says. “And those are definitely the qualities that being a distance runner can instill in you.”

Stubna’s lab mates have come up with a unique test of his speed. “Because I’m trying to stay in competitive running shape, people in my lab have proposed a relay race in which I run one mile on the track versus eight of them running 200 meters each,” he says. “I think I’m going to get destroyed, but I’ll try to run a mile in 4:45 and see what happens.”

While training for events takes time and commitment, beginners can reap the benefits of running, too. “Running is the easiest sport to get into late in life,” Kingston says. “If you didn’t play a sport growing up but you want to start getting active, running is a great way to do that. It gives you a lot of flexibility. You can fit in a run whenever you have the chance.”

“It’s a time when it’s just you, with yourself,” she adds. “You have the ability to think things through, to be outside, and if you want to just shut your mind off. All of those things are helpful. At times, I’ve used running to think through a problem, but I’ve also used running to just be out in nature and not think about work.”

The mental and physical health benefits of running have become even more important during social distancing amid the COVID-19 outbreak, Kingston says. “It’s probably the thing that’s keeping me sane right now,” she says. “But it also feels even more like a luxury or privilege right now—the fact that I’m still healthy and can go out for a run seems more special.” Early morning runs have been helpful in avoiding peak times for crowds, she says. To cope with working at a desk rather than the more dynamic lab environment, Kingston recommends alternating 50-minute work periods with 10 minutes of moving around at home.

"Running is a great opportunity to get mental and physical distance from your local environment and thought processes,” Knouse says. “It really helps me to clear my head and open my mind to new things. Most of my ideas for projects and experiments come to me when I'm a few miles into a long run."

“Although many certainties I took for granted have changed for me in the last couple of weeks, regular running outside is not one of them, at least not yet,” Chmatal says. The Boston marathon, now postponed, had been the focus of his training, but he continues to log his mileage to stay grounded. “The importance of being outside (socially-distanced) and getting some fresh air while exercising has never felt so urgent,” he says. “It seems to me that every runner I pass while running these days outside has it written on their face.”

Topics

Contact

Communications and Public Affairs

Phone: 617-452-4630

Email: newsroom@wi.mit.edu