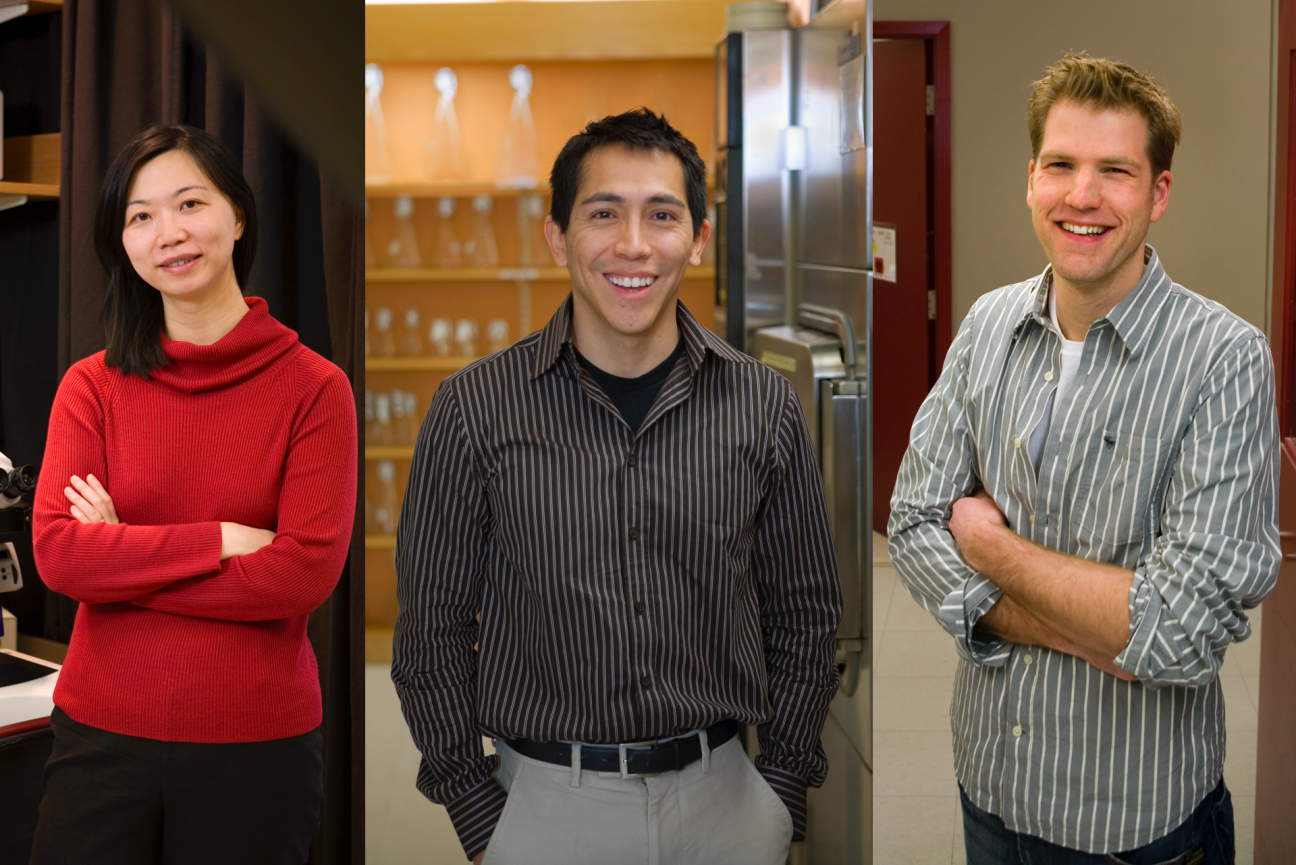

Hui Ge, Fernando Camargo, and Thijn Brummelkamp

Thijn Brummelkamp, Pam Francis and Sam Ogden

Fellows hit the fast track

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — It began as an experiment. Take a young scientist, unproven as an independent researcher, and give her the space, resources and support needed to launch a lab. Challenge her to take a risky project from idea to reality under her own steam. Then, as with any good experiment, examine the results.

Twenty years later, this experiment—known as the Whitehead Fellows program—has succeeded in proving that a little risk can go a long way toward launching blockbuster careers.

“I believed that there were certain rare people who could take advantage of a program that gave them independence without the responsibility of a faculty member,” recalls Nobel laureate David Baltimore, who launched the program in 1984 when he was Whitehead Director. “I can only marvel that what was an impulsive experiment has been so generative of great people in science.”

"The program gives Fellows the opportunity—in a relatively protected environment—to pursue ideas and projects that are riskier than those undertaken in a traditional postdoc."

The latest class—Thijn Brummelkamp, Fernando Camargo and Hui Ge—recently began their tenures as Whitehead Fellows, following in the footsteps of such world-class scientists as David Bartel, Peter Kim, Eric Lander and David Page. With a little luck and a lot of audacity, the Fellows program will be a career-defining opportunity for the trio, who are coming from around the world to take part in Baltimore’s great “experiment.”

Out of the gates

Fellows are given the space, resources and freedom to run their own laboratories, rather than being required to complete a traditional postdoctoral appointment in the lab of a senior researcher. Candidates cannot apply to become Whitehead Fellows. Rather, they are nominated by leaders in the research community who are familiar with each candidate’s work and academic accomplishments.

“The program gives Fellows the opportunity—in a relatively protected environment—to pursue ideas and projects that are riskier than those undertaken in a traditional postdoc,” says Whitehead Associate Member and former Fellow David Sabatini. “Fellows interact extensively among themselves and serve as each other’s best critics for new ideas.”

Unlike full-fledged faculty, Fellows have no teaching responsibilities. They use their time at the Institute to concentrate solely on building a strong research program.

The Fellows also gain invaluable experience managing their own laboratories. They start with Institute funding, but as their research matures, they find financial backing from federal grants and other sources.

“The opportunity to work independently early in my career as a Whitehead Fellow allowed me to develop my own research program and hone my skills in a way that is greatly accelerating my progress as an assistant professor,” says Nir Hacohen, who joined Harvard Medical School in 2003 after completing a four-year term as a Whitehead Fellow. “I entered my new position with a running start, with wonderful students and postdocs in my lab, and strong ties to the research community—all of which make a difference in my current work.”

Knocking out cancer

“Whitehead will be a fantastic place to do research,” says cancer researcher and Netherlands native Thijn Brummelkamp. “The most rewarding part of the Fellows program will be to work together with good and enthusiastic scientists.”

Brummelkamp spent several years in the laboratory of Rene Benards at the Netherlands Cancer Institute in Amsterdam, where he received his doctoral degree in 2003.

Cancer researchers say that the most important feature of an ideal anti-cancer drug is its ability to selectively target cancer cells while leaving the normal non-malignant cells untouched. One strategy has been to develop drugs that attack the genomes of cancer cells so that they can no longer grow and divide. In principle, this would destroy the cancer.

Unfortunately, many current cancer drugs aren’t specific enough and disrupt the growth and function of other cells in the body, producing the terrible side effects associated with chemotherapy.

Brummelkamp exploits a process called RNA interference (RNAi), which can selectively turn off specific genes, to study genes implicated in cancer. He and his colleagues hope to use RNAi to identify vulnerabilities in a cancer cell’s genetic make-up that can be targeted by new therapeutics.

“Thijn Brummelkamp has had a spectacular run as a student in Rene Bernards’s group,” says Whitehead Member Robert Weinberg. “Many of us are looking forward to having someone with his talents and energies among us.”

Bred in the bone marrow

Faced with limited opportunities to explore his love for science in his native Peru, Fernando Camargo came to the United States when he was 18 years old. He earned a scholarship at the University of Arizona in Tucson to complete a bachelor’s degree in biochemistry in 2000. He then moved to Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, where he was a star student in the graduate program in cell and molecular biology. Camargo, who received his PhD from Baylor in 2004, arrived at Whitehead in November.

“Fernando is an extremely creative scientist and a superb communicator, and has an unparalleled drive to succeed,” says Camargo’s graduate advisor Peggy Goodell. Goodell, now an associate professor at Baylor, worked at Whitehead as a postdoc in the early 1990s. “He has both the scientific and personal maturity to excel as a Whitehead Fellow, and is guaranteed to enrich the Institute during his tenure.”

Camargo is working to understand the basic molecular mechanisms that control cells known as hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs). Found in human bone marrow, HSCs have the uncanny ability to differentiate into several kinds of essential blood cells, such as blood-clotting platelets and infection-fighting lymphocytes. Camargo is studying the mechanisms underlying HSC “plasticity,” the term used to describe a stem cell’s unique ability to transform into many different cell types.

A deeper understanding of these mechanisms may help advance efforts to use sem cell therapy to repair damaged tissues and treat disease.

“The therapeutic potential of stem cells is tremendous, but there is still a big gap in basic knowledge that needs to be filled before stem cell biology can move into the clinic,” says Camargo, who also studied medicine in Peru early in his career. “I would like my research to be a major contributor to bridging this gap.”

Worms (wet and dry)

Like Camargo, new Fellow Hui Ge has followed her love of science many thousands of miles from her childhood home. A native of China, Ge came to the U.S. in 1999 when she was selected for a Fu Fellowship, which supports Chinese students studying at Harvard. Ge eventually found her way to Marc Vidal’s lab at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute, where she earned her PhD in 2004.

Within Vidal’s lab, Ge conducted studies aimed at understanding how proteins interact with each other. In one experiment, Ge and her colleagues devised a way to examine how certain protein interactions are conserved across evolution. The team showed that conservation of these interactions among yeast and worms—two systems commonly used to study human biology—was surprisingly high.

Ge is part of a new generation of scientists working to integrate bio-informatics studies with traditional biological experiments—a division often described as “dry lab” versus “wet lab” work. She wants to use an integrated laboratory approach to study gene and protein function, work that she hopes will advance understanding of human health and disease.

“Because of the information generated by the human genome sequence, biology increasingly is becoming an informational science,” says Ge. “But the way it is now, bioinformaticians have dry labs and biologists have wet labs, creating a lack of communication between the two. In my lab I want to use computational approaches to generate hypotheses that I can then check in a real model in a wet lab.”

Because most of Ge’s experience has been in computational science, she is spending a short time in Craig Hunter’s lab at Harvard to garner more experience working with the worm C. elegans, the animal model she will use in the wet lab component of her work. Ge will launch her lab at Whitehead in early 2005.

“My lab at Harvard was very big, so I am used to working independently,” says Ge. “But Whitehead Institute provides an amazing environment, and I think that the Fellows position will give me a very good transition into an independent career.”

“I am happy that Hui will be able to continue her training while starting her own line of research at the Whitehead Institute,” says Marc Vidal, assistant professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School, whose lab she worked in as a graduate student. “Her ability to address biological questions both experimentally and computationally is a particularly great asset.”

Trial by fire

The Fellows program isn’t for every investigator. Fellows are not part of a lab, they are the lab.

“Playing a managerial role will be totally new to me and probably the most challenging part of being a Fellow,” says Ge. Like all new Fellows, she has never hired anyone, let alone run a group.

Being a Fellow means managing budgets, attracting and hiring people to work in the lab, managing them and serving as the lead author on prospective publications. No matter how collegial and supportive the environment, Fellows must have the confidence to forge their own research path. And as their research program matures, they will also face the challenge of raising funds through competitive grants.

Current Fellows Mark Daly and Ernest Fraenkel have successfully made this transition. “The generous support of the Whitehead Fellows program enabled me to take off in a new scientific direction,” says Fraenkel. He is combining structural analysis, bioinformatics and biochemistry to predict the interaction of proteins—work that will ultimately lead to a better understanding of the biology of cancer and human development.

Mark Daly’s lab focuses on understanding patterns of variation in the human genome and translating that knowledge into more effective statistical methods for finding the variation responsible for specific diseases. “The Fellows program gave me the invaluable opportunity to explore my ideas in a uniquely unrestrained environ-ment,” says Daly. “The support of the Institute in my scientific work and career development through this program has been immeasurable.”

Like Daly and Fraenkel, new Fellows will receive mentorship from senior Whitehead researchers and have unfettered access to the Institute’s scientific and administrative resources.

Perhaps more importantly, they have each other.

“One of my favorite parts of being at Whitehead was working with other Fellows—all young, energetic and smart scientists who really wanted to solve important biological problems,” comments Hacohen. “This is the kind of community that needs to be encouraged in all institutions because it accelerates scientific progress and makes it more fun to do science.”

by Melissa Withers.

Topics

Contact

Communications and Public Affairs

Phone: 617-452-4630

Email: newsroom@wi.mit.edu