Variations in cell programs control cancer and normal stem cells

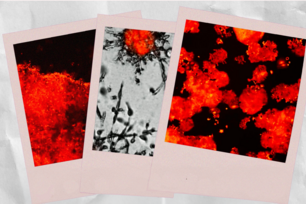

The gland reconstitution mammary stem cells and breast cancer stem cells utilize different epithelial-to-mesenchymal (EMT)-inducing transcription factors and reside in different cellular states. Normal mammary stem cells rely on the Slug EMT-inducing transcription factor for stemness and are partially epithelial and partially mesenchymal. In contrast, breast cancer stem cells express the gastrulation EMT-inducing transcription factor Snail and reside in a far mesenchymal state.

Courtesy of Xin Ye

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. – In the breast, cancer stem cells and normal stem cells can arise from different cell types but tap into distinct yet related stem cell programs, according to Whitehead Institute researchers. The differences between these stem cell programs may be significant enough to be exploited by future therapeutics.

Deadly tumor-initiating cells seed metastases throughout the body and cause relapses in patients. Whether these tumor-initiating cells can also be referred to as stem cells, specifically, cancer stem cells, has been up for debate. The question is not purely one of semantics—the label connotes scientists’ understanding of those cells’ identity and inner workings.

“Our research establishes for the first time the relationship between the normal stem cell program and the cancer stem cell program, albeit in the context of the mammary gland,” says Whitehead Institute Founding Member Robert Weinberg. “There may be slight variations on this theme in other epithelial tissues, but at least the relationship is firmly secured in the context of the mammary gland, which seems to be a pretty good model for other epithelial tissues. Tumor-initiating cells are in fact cancer stem cells, but cancer stem cells do not arise from normal stem cells.”

The Weinberg lab’s findings are described in this week’s issue of the journal Nature.

Previous work in the lab has demonstrated that cancer stem cells emerge after undergoing an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which endows the cells with the motility and flexibility required for seeding new tumors. The EMT may also confer on the cells the ability to resist standard chemotherapeutics.

In the current line of research, Xin Ye, who is a senior research associate in the Weinberg lab and the lead author of the Nature paper, used a mouse model that shows which cells within the normal and cancerous mammary gland express the related master regulators Snail and Slug, both of which confer stem-like traits on mammary cells. Slug, for its part, is especially potent in inducing the “mesenchymal” cell traits that are associated with high-grade, aggressive carcinomas.

Ye determined that different cell types in distinct tissue layers within the mammary gland express and are influenced by these master regulators. Slug, which regulates gland-reconstituting activity in breast tissue, is expressed at higher levels in normal stem cells found in the ‘basal layer” of mammary ducts. Snail, a factor first discovered in the context fruit fly embryonic development, is expressed by tumor-initiating cells in the luminal layer of cells in these ducts. Snail has the power to confer aggressive traits on cancer cells that Slug is incapable of doing when it is expressed at normal levels.

“Snail-positive cancer stem cells arise in a different population of cells than the cells that harbor normal stem cells,” says Weinberg, who is also a professor of biology at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Director of the MIT/Ludwig Center for Molecular Oncology. “Normal stem cells reside in one layer in the mammary duct; cancer stem cells arise in another. What that means is that cancer stem cells do not arise from normal stem cells. This has been a point of much discussion, but now there is evidence—finally!”

Such basic insights about the source of cancer stem cells and the differences between normal and cancer cells could provide leads for new cancer therapeutics.

“We’re starting to realize that a lot of things are regulated differentially in normal versus cancer settings,” says Ye. “It doesn’t even need to be cancer stem cell versus normal stem cell—cancer versus normal is really different. If we understand the differences better, we have a better chance of treating this disease.”

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation, Singapore (NRFNRFF2015-04), American Cancer Society, Ludwig Foundation, Breast Cancer Research Foundation, National Cancer Institute Program (P01-CA080111, U01-CA184897, R01-CA078461, K99-CA194160), Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation, Mattina R. Proctor Foundation, Helen Hay Whitney Foundation, and Andria and Paul Heafy.

* * *

Robert Weinberg’s primary affiliation is with Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, where his laboratory is located and all his research is conducted. He is also a Professor of Biology at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Director of the MIT/Ludwig Center for Molecular Oncology.

* * *

Citation

Ye, X., Tam, W. L., Shibue, T., Kaygusuz, Y., Reinhardt, F., Eaton, E. N., & Weinberg, R. A. (2015). Distinct EMT programs control normal mammary stem cells and tumour-initiating cells. Nature, 525(7568), 256-260.

Topics

Contact

Communications and Public Affairs

Phone: 617-452-4630

Email: newsroom@wi.mit.edu