BioGenesis Podcast: Alicia Zamudio of the Young lab on Changing Majors and Exploring Transcription

Introducing BioGenesis: a new podcast from MIT Biology and Whitehead Institute where we get to know a biologist, where they came from, and where they’re going next. In each episode, co-hosts Raleigh McElvery, Communications Coordinator at MIT Biology, and Conor Gearin, Digital and Social Media Specialist at Whitehead Institute, introduce a different student from the Department of Biology, and — as the title of the podcast suggests — explore the guest’s origin story.

Season 1 focuses on stories of surprise. In our second episode, graduate student Alicia Zamudio from Whitehead Institute Member Richard Young’s lab shares her story of moving from Mexico to the U.S. to study psychology and become a writer — until she discovered a new passion that seemed like something out of science fiction.

AUDIO

Subscribe to BioGenesis on iTunes, Spotify, Google Play, or SoundCloud to keep up with season 1!

EDITED TRANSCRIPT

Alicia Zamudio: I think what drove me into gene expression is this fascination with understanding who we are at a molecular level because the expression of genes determines if you are a neuron or you are a skin cell. Therefore if you can't express the very specific genes that define neuronal lineage you can't be exactly who you are.

Raleigh McElvery: Welcome to episode 2 of “BioGenesis,” where we get to know a biologist, where they came from, and where they’re going next. I’m Raleigh McElvery from the MIT Department of Biology —

Conor Gearin: And I’m Conor Gearin from Whitehead Institute —

McElvery: And together, we’re showing you the people behind the biology by introducing you to one scientist each episode.

Gearin: Our first season focuses on surprises. Last week, the surprise was a new direction for a research project.

McElvery: Today, grad student Alicia Zamudio tells us about the unexpected turn that her career path took in college, which led her to ask big questions about how our genes are regulated.

Zamudio: My name is Alicia Zamudio. I am a fourth-year grad student in the biology department and I work in Richard Young's lab at the Whitehead Institute. I grew up in Mexico City, Mexico, which is in central Mexico. And it's a big city. It's bigger than New York. There are about 20 million people that live there or so. And I grew up with a very traditional Mexican family of working class people. And we didn't really meet any scientists or have any people in our family that did any sort of academic professions. I think most of the people that I grew up with did something related to business or had their own shops or sold their own things.

McElvery: Like a lot of kids, Alicia grew up watching Disney movies —

Zamudio: — including The Beauty and the Beast, that was one of my favorites —

McElvery: — but unlike many, she didn’t dream of being a princess.

Zamudio: I think when I was very little I really wanted to be an inventor like Belle's dad. I just thought that would be cool to make something. And I never realized that that could be an actual profession.

Gearin: She actually considered quite a few different professions early on.

Zamudio: Actually when I started college I had the intention of being a writer and I decided to major in psychology with the intention of understanding how humans behave better in order to write better about humans.

McElvery: Alicia knew she wanted to apply to college in the US, but wasn’t quite sure how to go about it initially.

Zamudio: No one in my family had really applied to college in the U.S. So I just literally like went on Google and found College Board, which is this website that essentially provides like some information about college and how to apply there. And I got all of my information on how to apply based on that one website.

McElvery: She ultimately selected San Diego State University, which was far enough away to feel different but still close enough to her family in Mexico.

Zamudio: And I'm actually very happy that I decided to go there because it was a place where there is incredible diversity, both racially and then religious diversity. There are veterans there, there are people from all sorts of walks of life and different ages.

Gearin: Although she entered SDSU intending to understand human behavior through writing, her quest actually led her away from the humanities, towards an entirely different department.

Zamudio: And I thought psychology would be just a great way of understanding behavior better and being able to write about human behavior and write more compelling stories in the future.

Gearin: That is, until her sophomore year.

Zamudio: I took this neurophysiology class with the best professor that I've ever had. For example, the first day of classes, she showed us a video of this monkey, and this monkey had an implant in his brain that allowed it to control this robotic arm that was essentially like a foot away from it. And I thought that was amazing. I just had no idea that that was possible. I thought that was like something that could only happen in science fiction.

McElvery: She became captivated by this experiment. She started thinking — could she herself help turn sci-fi into reality?

Gearin: Pursuing a minor in biology in addition to her psychology major seemed like the way to go.

Zamudio: So one of the people that I spoke to was the director of the biology major I at SDSU. I essentially just wanted to get a minor because I wanted to, literally just for my own curiosity, I wanted to get a little bit of a feel of what biology was like, of what physical science had to say about human behavior. And he suggested that I take on biology as a major. He said: You know, if you decide that you don't want to do it in the future, you can just drop it and just leave it as a minor. But at the moment I'm going to sign you up as an official major and then I'll let you decide.

McElvery: She ended up keeping the double major, and started working in the lab of professor Ralph Feuer.

Zamudio: His lab was studying a virus not really neuroscience but the virus infects the nervous system.

Gearin: And she found resources that would even let her be paid for her time in the lab.

Zamudio: They have these programs that help minority students essentially get into grad school. So I applied to one of these programs. I was very fortunate to be admitted into it, and it paid me for working about 20 hours a week in the lab.

Gearin: The day she got the scholarship was the same day she gave her 2 week notice at the GAP store she’d been working at for the past three years to support herself. She could now focus primarily on research.

Zamudio: And it ended up being a really good experience because I learned like most most the most basic molecular biology techniques and way of thinking. And I think it was at that point where I realized that I was really interested in very basic questions that at the end of the day still relate to neuroscience in the sense that every single cell in your body cares about the way that genes are expressed.

Gearin: Suddenly, Alicia wasn’t just pursuing her curiosity. Her career was heading in a direction she’d hadn’t imagined before. She was becoming a biologist with an interest in fundamental questions. And then she heard a TED Talk by Angela Belcher, a professor in MIT’s Department of Biological Engineering and a member of the Koch Institute. That TED Talk helped accelerate her transformation.

Zamudio: And I think what what struck me about it is that not only was her science incredible, I was impressed by, you know, a strong independent woman leading a lab, giving a talk, sounding incredibly intelligent doing what is clearly groundbreaking research. That's one thing. But in addition to me learning about some cool science, I also got to hear her description of this visit that the president had done to her lab.

McElvery: And that got Alicia thinking about MIT.

Zamudio: That made me made me feel like: Oh my God if I could work there, that would be incredible. Like imagine how productive your day would be if you got do research that the president cares about. I think that's incredible.

McElvery: So Alicia applied to MIT’s Summer Research Program in Biology and Brain & Cognitive Sciences. She got in, and spent a summer at MIT’s Picower Institute working for professor Li-Huei Tsai.

Gearin: She was totally blown away by the resources available to her.

Zamudio: I just remember walking in there and like immediately texting the master's student that worked in my lab and I was like: Hey they have a temperature-controlled microscope here. I was so excited about it. It's like, oh we would kill for this you know. And it was just night and day in terms of the types of experiments that they do you get to do here. I didn't want to be limited by our budget. I wanted to be limited by the breadth of our ideas. And I think that's what drove me to apply to grad school.

Gearin: But she still had to finish up her double major at SDSU. Although it would add an extra year onto her undergrad education, she found a way to have both MIT and SDSU at once.

McElvery: She was invited to come back to MIT to do research and take classes while she finished up her SDSU degrees online.

Zamudio: I did research for the whole seven months and it was incredible.

McElvery: She had to open 2 credit cards to pay her rent, but it was worth it.

Zamudio: It was like literally three literally the first time that I felt like yes, 100 percent, I can do grad school, this is like the type of thing that I want to be doing. I'm not only like competent enough to do this, I also I also enjoy it.

McElvery: When Alicia told her parents that she wanted to go to MIT, they didn’t quite get it. At least, not at first.

Zamudio: No one in Mexico really has heard of M.I.T. with few exceptions. They don't really get to hear about M.I.T. They know about Harvard. And so I applied to Harvard. I got accepted into two programs at Harvard, and I think that was a time where my parents were incredibly proud of me. They were like: Wow, everything we've done, we've done right. And in spite of that, I still came to MIT, because I thought this was the best place for me to do science. I really like the community. I like the science that I experience here. I wanted to be in a place where you actually get to feel like you're part of a community, and I think the fact that you know exactly who that person works for, and you know someone in that lab, it really helps you feel like you are a part of something greater. So I really like that. And then interacting with the students, everyone was very down to earth. I wanted to be around people that are generally motivated, smart, and also a little bit humble.

Gearin: Alicia’s work in Li-Huei Tsai’s lab had gotten her interested in the way DNA is packaged within the cell, and how that impacts which genes are expressed or not.

McElvery: That’s right, and one of the leading researchers in this field happened to be a professor at MIT Biology and a member of Whitehead Institute: Rick Young

Zamudio: I ended up rotating in three labs. He was the only person that was really doing gene expression research. And I just loved the environment. So Rick runs his lab a little bit like a company, which means that people there behave a little bit more professionally than your average grad student or postdoc. So they dress a little bit more professional. They're a little bit more, like, determined and I just like really like that environment.

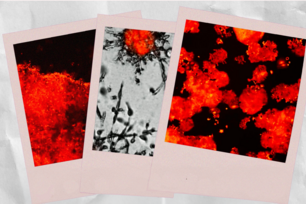

McElvery: Their recent studies have shown that the proteins that regulate key genes that determine cell identity aren’t just floating around inside the nucleus. They actually form compartments called membraneless organelles.

Gearin: Some people compare them to pearls or droplets.

Zamudio: It’s literally just something that looks like it has a structure that does not have a membrane. A lot of people have seen diagrams of cells in biology textbooks. You usually have a gigantic cell that is encapsulated by a membrane, and then you have a smaller membrane-bound compartment which is the nucleus. So imagine that you had like a nucleus inside of the nucleus. That is literally when we're trying to describe. Just like small compartments within cells that are are concentrating a bunch of factors that are important for transcription.

Gearin: Some of the proteins involved in transcription have domains that don’t form a stable structure.

Zamudio: People talk about it as spaghetti or noodles — many ways of describing it. So essentially it's just it's just a portion of a protein that just does not acquire one particular conformation.

Gearin: And it’s the lack of a stable structure that lets these proteins behave like fluids and form membraneless organelles. That process is called phase separation. It’s similar to when oil separates and forms droplets in salad dressing.

McElvery: Alicia and her colleagues took every protein they could imagine that might be involved in gene transcription, and used algorithms to predict which of these proteins had disordered regions and could form the droplets.

Gearin: They started with one that looked promising — beta catenin, a signaling protein that’s key to development as well as cancer. Alicia and her colleagues ran experiments that showed the protein did form membraneless organelles, both in test tubes and live cells.

Zamudio: And we started wondering if it was in fact not a property of just this particular signaling factor that allows it to form these membraneless organelles, but we tried to figure out if other components of different signaling pathways are also able to do this.

McElvery: The team expanded their search to three other proteins from other crucial signaling pathways.

Zamudio: And we were able to demonstrate that all of these three different components are able to form these membraneless organelles, they do this at the cell identity genes, and we think that is important for their function and eventually for the proper activation of genes that are regulated by those pathways.

Gearin: These findings had an application for cancer biology, in which cancer-causing genes called oncogenes are activated at the wrong times. As the team made progress on this new model of transcription, Alicia’s childhood dream of being an inventor wasn’t so far away anymore.

Zamudio: So we have a filed a provisional patent for phase separation. So essentially it is the discovery and the application of phase separation in transcription. This idea that we can try to decrease the expression of oncogenes I think sounds like science fiction to me as well.

McElvery: Alicia is getting to do science that would have made her childhood self proud.

Zamudio: I guess I should tell my 6-year-old self that I was able to actually get that little dream to become true. It's kind of cool.

McElvery: And she’s volunteering her time to make sure other people get the same opportunities.

Zamudio: It's 100 percent important to me to support any type of program that helps students who come from disadvantaged backgrounds, whether that is minority backgrounds, whether that is a financial disadvantaged background, whether that is a first generation student — all of those things that I struggled with. I just want to make it a little bit easier for people who come from any of these types of complicated backgrounds to to do well either in college or in grad school.

McElvery: That’s it for this week. For our next episode on “Surprises,” come back next week to hear how a student who thought she wanted to go into genetic counseling realized that she had a passion for figuring out how cells work at a fundamental level.

Gearin: Find us on iTunes and SoundCloud or on our websites at MIT Biology and Whitehead Institute.

McElvery: Thanks for listening.

***

Music for this episode came from the Free Music Archive, Blue Dot Sessions at www.sessions.blue, and Podington Bear at soundofpicture.com. In order of appearance:

“Something Elated” – Broke for Free

“Many Hands” – Podington Bear

“Ant Farm” – Podington Bear

“Bright White” – Podington Bear

“Pretty Build” – Podington Bear

“Anders” – Blue Dot Sessions at

“Soothe” – Blue Dot Sessions at

“Arizona Moon” – Blue Dot Sessions

“Trundle” – Podington Bear

Topics

Contact

Communications and Public Affairs

Phone: 617-452-4630

Email: newsroom@wi.mit.edu